To what extent does financial capability factor into the issue of hunger? Why?

Abstruse

This study investigates the components and mechanisms of the fiscal capability framework using national representative data from the 2015 National Financial Adequacy Study with the structural equation modeling arroyo. We find fiscal socialization and fiscal instruction are significantly associated with both financial access and financial literacy, which are associated with positive financial behavior and negatively associated with economical hardship. We further find that fiscal access plays a more pronounced part in the mediation effects decomposition compared to financial literacy. Our findings demonstrate that financial capability lies in both the opportunity to human action and the ability to act—with opportunity relatively more of import than ability—and that financial capability is strongly associated with household experiences of economical hardship. Policies and programs should provide attainable and affordable financial products as well as raise effective financial instruction and guidance to promote fiscal inclusion.

Introduction

Economic hardship among U.S. households is on the ascent. A 2019 national survey showed that 28% of respondents could not cover their current monthly bills in full or would neglect to do so should they accept a pocket-size emergency, and 25% reported skipping medical intendance considering of inability to afford the cost of care (Canilang et al., 2020). To make matters worse, emerging data show a sharp ascension in economic hardship among U.South. households during the COVID-19 pandemic (Canilang et al., 2020; Despard, Frank-Miller, et al., 2020; Despard, Grinstein-Weiss, et al., 2020; Parrott et al., 2020). Increased financial adequacy can reduce economic hardship through enhanced financial knowledge, access to savings and credit, and optimized financial decisions and behaviors (Huang et al., 2015a, 2015b; Johnson & Thousand. S. Sherraden, 2007; M. Due south. Sherraden, 2013). The importance of financial capability is supported past the American Academy of Social Work and Social Welfare (AASWSW), which adopted "fiscal capability and asset edifice for all" (M.S. Sherraden et al., 2016) every bit one of 13 one thousand challenges for social work (Fong et al., 2017).

M.South. Sherraden et al. (2016) point out that ii primal trends determine financial capability's significance. The offset is that the financialization of daily life requires everyone to accept financial skills and knowledge to bargain with daily fiscal matters, such equally purchasing and selling assets or products, also as organizing and managing their money, such as bank accounts, credit cards, and savings (Martin, 2002). The second is that labor income has grown stagnant and increasingly unstable, and at the aforementioned time, has increased the importance of owning assets. Therefore, people need access to policies, products, and services to stabilize and secure their economic well-being.

Researchers have investigated how financial pedagogy and socialization contribute to fiscal capability (due east.grand., Fernandes et al., 2014; Lusardi, 2011; Stolper & Walter, 2017). Others have highlighted the empirical connections between fiscal capability and lower gamble of economic hardship (e.grand., Birkenmaier et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2015a; Huang, Nam, et al., 2016; Huang, M.S. Sherraden, et al., 2016; West & Friedline, 2016). All the same, to the best of our knowledge, no study has empirically tested the financial capability framework comprehensively using nationally representative data in the U.s.a.. One study used data to test the full financial capability model (Chowa et al., 2014), but it relied on a nonrepresentative sample from a commune in Uganda. Other studies pertinent to this topic lack comprehensive measures of the core components of the financial capability framework (e.g., Lusardi, 2011). Further, the relative importance of financial access and financial literacy in the financial adequacy framework is unknown in existing empirical studies. Yet, from a practice and policy perspective, knowing the relative importance of these two constructs could inform the appropriate design and targeting of interventions to improve private and family financial well-being.

Accordingly, this study investigates the underlying mechanisms and components of the fiscal capability framework using national representative data from the US. Nosotros foremost examine the adequacy of the multi-item measures of each of the core components of financial adequacy—i.e., financial literacy, financial access, and financial behavior. Further, we examination the structural relationships among the financial capability cadre components and their connections to economic hardship. Finally, we examine the relative importance of financial literacy and financial access among these relationships and pathways. We aim to present a comprehensive review and assay of the fiscal capability framework. Below, we review research on determinants and components of financial capability—financial socialization, financial education, financial literacy, and financial access—and evidence on the relationship between financial capability and economic hardship.

Conceptualizing fiscal capability

Fiscal capability, which combines people's power to act and opportunity to act, emphasizes both private cognition and behavior, too as the structural environment (i.e., availability of services and products) (Chiliad. S. Sherraden, 2013). Fiscal capability is conceptualized as a combination of financial literacy, financial admission, and financial behavior (Huang et al., 2015a, 2015b; M. S. Sherraden, 2013). In the financial capability framework, K.Due south. Sherraden (2013) makes a compelling case that financial capability should focus on both internal and external factors that intrinsically influence people'due south power and external contextual factors such as institutions and policies that enhance the opportunity to access financial services and products. In other words, financial capability is multidimensional every bit it combines individual internal ability and external conditions (Nussbaum, 2001, 2011). Researchers measure financial adequacy differently with selected indicators without justifications or consensus. For case, some studies measure financial capability using financial behaviors such equally making ends encounter, planning ahead, and money direction (e.thou., Taylor, 2011), whereas other studies apply financial literacy (due east.g., Lusardi, 2011) every bit a proxy for financial capability. All the same, improving ane's fiscal behavior requires possessing knowledge and skills, every bit well as having access to financial products and services. A more comprehensive mensurate of financial capability has the potential to inform future research, policy, and practice in this field.

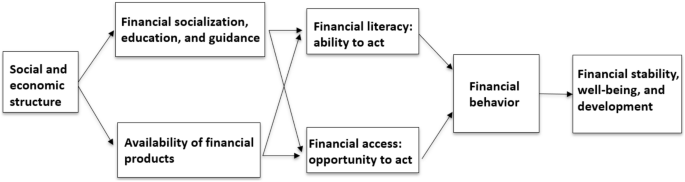

This paper measures fiscal capability past combining three components: financial literacy, financial admission, and fiscal behavior. Under the financial capability framework (Fig. 1), social and economical structures generate financial socialization opportunities in the family unit and financial education at schoolhouse and in the workplace. Financial socialization and education opportunities, in plow, affect people'southward fiscal capability. People with greater levels of financial capability are equipped with financial knowledge and skills, and have access to financial services and products, and thus have meliorate fiscal behavior, which in plow contributes to a wide range of outcomes, including financial stability, well-being, and development (M. Southward., Sherraden & Huang, 2019).

adapted from Thou. S. Sherraden (2013)

The financial capability framework,

Fiscal Socialization and Fiscal Pedagogy

Financial socialization, as defined by Schuchardt et al. (2009), is values, attitudes, standards, norms, knowledge, and behaviors that guide members, peers, and media (Elder & Giele, 2009; Schuchardt et al., 2009). As they grow up, individuals gain unlike levels of financial socialization. Parents model and teach their children different things virtually financial management depending on their fiscal position and experiences. Wealthier parents, who are more likely to have feel with mainstream financial products, are more than probable to share this information and their experiences with their children (Stacey, 1983). In contrast, parents with depression incomes may have less (or negative) experience with mainstream financial services, and may avert discussing details of the family'south financial distress with their children (Grand. S. Sherraden & McBride, 2010). Jorgensen and Savla (2010) found perceived parental influence had a direct and moderately pregnant influence on financial attitudes, an indirect and moderately significant influence on financial behavior, a mediated effect through fiscal attitude, and no effect on financial knowledge.

In addition to socialization, people at all life stages may benefit from financial pedagogy, guidance, and advice to bargain with complex financial matters and attain financial well-being. A wide range of financial programs offered by schools, employers, and financial institutions have emerged to answer to this need. Existing financial teaching programs have a broad range of objectives, audiences, timing, contents, and designs. The effectiveness of these programs is positive overall, although in that location are mixed evidence and variations to consider (Collins & O'Rourke, 2010; Fernandes et al., 2014; Kaiser & Menkhoff, 2019). For example, Collins and O'Rourke (2010) reviewed 41 evaluations of financial education and counseling programs that serve adult populations, including general financial education programs, bankruptcy programs, credit repair programs, prepurchase homeownership counseling, mail service-purchase mortgage counseling, and workplace-based programs. They point out limitations in well-nigh studies, including self-reported evaluations, tracking outcomes over a short menses, selection bias in causal inferences, lack of theory-based evaluations, and lack of randomized field experiments (Collins & O'Rourke, 2010).

Yet the limitations of intervention studies, the conceptual pathway from fiscal socialization and financial pedagogy to financial literacy is compelling and supported past information (Lusardi, 2019; Xiao & O'Neill, 2016). In this written report, we leverage a large, nationally representative sample to replicate this relationship but as well examine the implications of these relations for fiscal access, fiscal behavior, and material hardship.

Financial Literacy and Financial Access

Researchers and policymakers oft use financial adequacy and financial literacy interchangeably and make no distinction between the 2. Notwithstanding, fiscal literacy is but one crucial component of financial capability. As divers by Danes and Haberman (2007), financial literacy is ''the power to interpret, communicate, compute, develop contained judgments, and take actions resulting from those processes to thrive in our complex financial world'' (p. 49). Huston (2010) distinguished between financial knowledge and financial literacy, where in improver to possessing the knowledge acquired through didactics and experiences well-nigh personal finance concepts and products (i.e., the knowledge dimension), there is an application dimension (i.east., the ability and confidence to apply or use the noesis effectively).

Fiscal literacy may be measured using both objective and subjective elements. Lusardi and Mitchell (2007, 2008) developed an objective measure of fiscal literacy, initially designed for the 2004 health and retirement study. This measure has been added to many surveys in the United States and abroad. Allgood and Walstad (2016) examined both objective and subjective measures and found that perceived financial literacy may be as of import every bit bodily fiscal literacy in influencing people'due south financial decisions and behavior.

Co-ordinate to Birkenmaier et al. (2019), financial access aims to achieve financial inclusion, where all people in a society can access and be empowered to use safe, affordable, relevant, and convenient financial products and services. Due to historical and current unjust social and economic structures, not anybody has access to products and services such equally savings accounts, credit cards, investment accounts, mortgages, small business loans, or small-dollar loans (Birkenmaier et al., 2019). Financially excluded households—who lack appropriate and accessible mainstream cyberbanking products and credit services—frequently turn to alternative fiscal services (AFS) with higher costs and predatory practices (Bradley et al., 2009).

Institutions provide opportunities available for people to admission financial products and services. Institutional theorists assert that depression-income individuals and families have depression levels of financial capability primarily because they do non take the same institutional opportunities that higher-income households accept (Beverly et al., 2008; Curley, et al., 2009; M. Sherraden, 1991; Yard. Sherraden, et al., 2003). Institutional-level factors that can expand opportunities include access, information, incentives, facilitation, expectations, restrictions, and security (Barr & M. Sherraden, 2005; Beverly & Grand. Sherradden, 1999; Beverly et al., 2008; G. Sherraden et al., 2003; Chiliad.South., Sherraden et al., 2004; Ssewamala & M. Sherraden, 2004). The construct of access refers to institutional mechanisms that make financial services or programs available to everyone.

How practise financial literacy and fiscal admission interact? Researchers have plant that private characteristics (e.grand., financial knowledge) are correlated with greater financial adequacy, provisional on appropriate institutional arrangements. Evidence from SEED for Oklahoma Kids (SEED OK), a long-term randomized experiment on child development accounts (CDAs), demonstrates that participants' fiscal knowledge is positively related to 529 college savings plans business relationship holding in the treatment group merely not in the control group (Huang et al., 2013). Another written report that examined savings amount and total asset corporeality every bit outcomes finds similar patterns (Huang et al., 2015a, 2015b). Significant interactions between treatment status (which represent institutional access, information, incentives) and fiscal knowledge are also establish, indicating that financial capability requires both improved individual financial knowledge and supportive institutional or policy arrangements. A recent study finds that compared to individual-level characteristics (eastward.one thousand., child poverty, child work, and attitudes towards savings), institutional-level factors (e.grand., access and proximity to banks, level of financial pedagogy) play a more pronounced role in influencing admission and utilization of fiscal services among poor HIV-impacted children and families (Lord's day et al., 2020).

Empirical Evidence on Financial Capability and Economic Hardship

Researchers who have examined the relationship between financial capability and economic hardships emphasize the office of financial access. Huang et al. (2013) analyzed financial capability and economic hardship among low-income older Asian immigrants in a supported employment program. They found that financial access and financial functioning are negatively associated with the gamble of experiencing economic hardship, whereas financial literacy is non significantly associated with economic hardship. Another study using data from SEED OK institute that fiscal capability, particularly the financial admission component, is critical for improving fiscal direction and reducing the risk of material hardship (Huang, Nam, et al., 2016; Huang, Sherraden, et al., 2016). Similarly, admission to liquid fiscal assets and revenue enhancement-time savings enable households to avoid hardship (Despard, Friedline, et al., 2018; Despard, Guo, et al., 2018; Gjertson, 2016; Grinstein-Weiss et al., 2016). The present study adds to this body of empirical evidence with a national representative sample, as well every bit antecedents of fiscal adequacy—financial didactics and financial socialization—in the model.

Research Aims and Hypotheses

Our study seeks to build on existing prove past using national representative data to investigate the financial capability framework's systematic components and underlying mechanisms, calculation the role of financial socialization and financial education as antecedents of financial capability. Moreover, we aim to compare the relative importance of financial literacy and financial access in a structural equation model.

Using nationally representative information, this study tests systematic components and underlying mechanisms of the fiscal capability framework. We hypothesize that both fiscal education and fiscal socialization are positively straight associated with two financial adequacy components: financial literacy and financial access (Hypothesis one; Antecedent hypothesis). Next, we hypothesize that financial access is relatively more predictive of financial behavior than financial literacy (Hypothesis 2; Comparative hypothesis). Lastly, we hypothesize that enhanced financial literacy and expanded financial access may reduce the take a chance of economic hardship via optimal financial behaviors (Hypothesis three; Indirect hypothesis).

Methods

This study uses data from the 2015 National Financial Capability Report. We mensurate financial literacy, access, beliefs, and economic hardship with latent variables and multiple indicators. Financial didactics and financial socialization are observed dichotomous variables. To test iii hypotheses, nosotros employ structural equation modeling approaches.

Data and Sample

Information used in this written report are fatigued from the U.S. 2015 National Financial Capability Study (NFCS) Land-by-Land Survey, funded past the Financial Manufacture Regulatory Authority (FINRA) Investor Pedagogy Foundation. The NFCS is a triennial cross-sectional survey beginning in 2009. It nerveless a nationally representative sample of approximately 27,000 individuals aged 18 and older, with about 500 respondents per country and oversampling for New York, Texas, Illinois, and California. The sampling quota was ready to approach the Census distribution that mirrors the distribution of age, gender, ethnicity, pedagogy level, and income within each state. We examined each study variable's responses and establish that a sizable number of respondents reported "don't know" and "prefer non to say" in the financial-related measures. Following prior enquiry (Xiao & O'Neill, 2018), we excluded these respondents, and the last analytical sample for both descriptive and SEM models was 24,154 respondents.

Measures

Tabular array 1 presents detailed measurements of all constructs. Our study's primal independent variables are financial education and financial socialization. Financial pedagogy is measured by whether the respondents' institution (e.g., school or workplace) offered fiscal instruction and whether the respondent chose to participate in such pedagogy. Respondents had three response options: (1) Yes, but did non participate in the financial education; (ii) Yeah, and did participate in financial education; and (three) No. We recoded this measure out by combining those who reported no with those who reported non participated in financial educational activity to construct a binary measure out that reflects whether respondents received financial education. Fiscal socialization is measured by whether respondents' parents or guardians taught them how to manage finance. Both financial education and financial socialization are dichotomous and are observed measures.

Guided by the building blocks of financial adequacy developed by M. S. Sherraden (2013), the endogenous variables—financial literacy, financial access, financial behavior, and economical hardship—are modeled as latent constructs. Financial literacy, representing the power to act, is a latent variable measured both by objective and subjective aspects of financial literacy. Objective financial literacy was measured past the sum of correctly answered six fiscal literacy questions. The original financial literacy questions were developed past Lusardi and Mitchell (2007, 2008), and now have been added used in more than 20 countries to measure financial noesis. Regarding subjective financial literacy, we followed Xiao et al. (2015) and utilized statements regarding their self-perceived overall financial noesis, and whether they are good at dealing with mean solar day-to-twenty-four hour period financial matters and practiced at math. All subjective fiscal literacy measures are ordinal (ane =strongly disagree; 7 =strongly agree).

Fiscal admission—a latent variable denoting the opportunity to act—is constructed based on the ownership of five financial products, namely checking, savings, and investment accounts, retirement program, and credit cards (Birkenmaier & Fu, 2019). We assess latent fiscal behavior based on respondents' fiscal direction practices and positive behavior in dealing with financial matters (Huang et al., 2015a, 2015b). We use two items to mensurate the construct: (a) a binary measure of whether respondents set aside plenty rainy-day funds to cover expenses for at to the lowest degree 3 months, and (b) an ordinal measure out evaluating whether they are setting long-term financial goals (1 =strongly disagree; 7 =strongly agree). Lastly, we followed Despard, Friedline, et al. (2018), Despard, Guo, et al. (2018), Despard, Taylor, et al. (2018)) to construct our latent economic hardship measure, an indicator of financial stability and well-beingness. The measure entails two items: a) an ordinal measure on whether respondents had whatever difficulty covering expenses and paying bills (1 =very difficult; ii =somewhat difficult; 3 =not at all), and b) a sum score of whatever difficulties in medical-related services such as non seeing a doc, non filling a prescription, and having unpaid bills from health intendance or medical service providers due to cost. Financial literacy, admission, and behavior are mediators and economic hardship is an outcome variable in this study.

Covariates related to financial literacy, access, behavior, and economic hardship, including gender, age, education level, marital condition, race, working status, and income, are controlled for in the analyses (Birkenmaier & Fu, 2019).

Statistical Analysis

Nosotros examine both the measurement model and a path model using the structural equation modeling (SEM) approach. SEM enables researchers to model complex relationships among observed and latent variables and obtain more precise estimates by accounting for measurement errors appraised by varied model fit index (Kline, 2015). To evaluate the appropriateness of the SEM model, we use multiple model fit indices, including comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with a ninety% confidence interval (CI). We utilise these fit indices in addition to model chi-square as they are sensitive and tend to be meaning when a larger sample is used (Wang & Wang, 2012). A good model fit for an SEM model is indicated past a non-significant chi-square, CFI and TLI > 0.90, and RMSEA < 0.05 with an upper bound of the ninety% CI < 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

The analyses are conducted in sequential steps. First, we utilize confirmatory factor analysis to examine the model fit of the measurement model past including all endogenous variables (i.east., financial literacy, financial access, fiscal behavior, and economical hardship). We then use a latent structure model to examine all the direct and indirect paths that connect observed variables of financial socialization and financial education (Hypothesis 1; Antecedent hypothesis), the three latent constructs for financial adequacy and economical hardship (Hypothesis 3; Indirect hypothesis) (encounter Fig. 1). The tests of significance of indirect effects are calculated using the delta method (Preacher & Hayes, 2008), which is more than appropriate when studies involve multiple mediators and a larger sample. To test Hypothesis 2 (Comparative hypothesis), we further utilize the consequence decomposition method for the indirect paths to examine the relative predictive role of financial education and financial socialization on the financial adequacy constructs. The weighted to the lowest degree foursquare mean and variance adapted (WLSMV) estimator is used for both measurement and path models to business relationship for the variables' binary or ordinal nature. We utilize weights for the path model so that the estimates can be generalized to the national profile. All the analyses were conducted using Grandplus vii.4.

Results

Table 2 presents the weighted demographic characteristics of the sample (northward = 24,154). The proportion of males (49.12%) and females (50.88%) are nearly every bit distributed. Respondents are mostly white (65.09%), married (59.59%), currently at work (55.04%), and with a college degree (including associate degree; threescore.41%). Age is virtually equally distributed across all age categories, and nearly a quarter of the respondents have income less than $25,000.

Measurement Model

Although the model chi-foursquare is significant, other indices reverberate a satisfactory model fit for the measurement model (χ 2 (55) = 2274.332, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.970; TLI = 0.958; RMSEA = 0.041 [ninety% CI: 0.039–0.042]). All the factor loadings are significant and higher up the 0.30 threshold (in standardized estimates). Similarly, the correlations across the four latent constructs are meaning at the 0.001 level: Financial literacy and fiscal access are positively correlated (r = 0.55, p < 0.001), and both latent variables are positively associated with financial behavior, with fiscal access showing a stronger relationship with financial behavior (r = 0.79, p < 0.001). Financial literacy (r = − 0.39, p < 0.001), financial admission (r = − 0.48, p < 0.001), and financial behavior (r = − 0.61, p < 0.001) are negatively correlated with economical hardship (Table iii).

Path Model

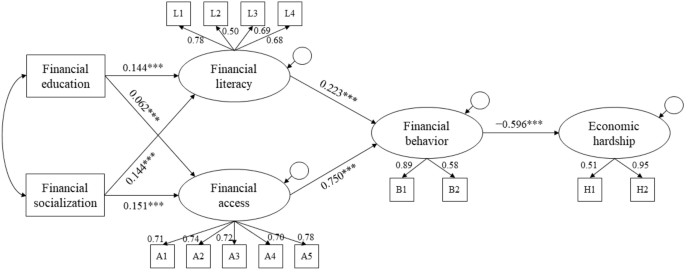

The latent path model (see Fig. 2) also shows a good model fit (χ 2 (135) = 4346.162, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.930; TLI = 0.900; RMSEA = 0.036 [ninety% CI: 0.035–0.037]), and all the standardized paths are statistically significant. Regarding the effects of control variables on each latent variable (results not shown in Figure), those who were males, older, with higher education, married, white, employed, and with higher income were generally establish to have higher levels of financial literacy, meliorate financial access, and lower economic hardship.

SEM results showing relationships between financial adequacy components and outcomes. Notes. Cistron loadings for each latent construct and path estimates were standardized estimates, and all of the estimates were significant at the 0.001 level All latent variables were controlled for covariates (gender, age, education, marital status, race, working condition, and income). Results (north = 24,154) were estimated using weighted to the lowest degree square to correct the categorical nature of indicators. Model fit: χ two (135) = 4346.162, p < .001; CFI = 0.930; TLI = 0.900; RMSEA = 0.036 (0.035–0.037). ***p < .001

For the focal variables of this study, both financial education and financial socialization are positively associated with financial literacy (β educational activity = 0.144 and β socialization = 0.144) and financial access (b education = 0.062 and b socialization = 0.151). The standardized path estimates evidence that both financial didactics and socialization accept a similar clan with fiscal literacy, but fiscal socialization has a stronger relationship with financial admission than financial education. Fiscal literacy (β = 0.223) and financial access (β = 0.750) have a positive association with financial behavior, which in turn, results in lower economic hardship (β = − 0.596). The standardized path estimates besides evidence that fiscal admission has a stronger predictive influence on fiscal behavior than fiscal literacy.

Relative Magnitude of Indirect Furnishings

Table 4 presents the indirect effects using the result decomposition method, and all the indirect effects are statistically meaning. Nosotros examined the relative magnitude of indirect effects from financial instruction and fiscal socialization to economic hardship via fiscal literacy, access, and behavior. Findings bear witness that fiscal education and financial socialization are positively associated with fiscal literacy and financial access, leading to better financial behavior and lower economical hardship. Withal, financial admission may play a more predictive part than fiscal literacy, every bit the size of the indirect path accounts for 60 to 78% of the total effect, whereas the proportion of the indirect effect involving financial literacy accounts for 22 to 40%. These findings propose that financial access plays a relatively more than predictive role than financial literacy in shaping household economic hardship.

Discussion and Direction

Both the multidimensional measure of fiscal capability with systematic components, and the test of mechanisms of the financial capability framework have a adept fit to the data—as confirmed by the structural equation models. We discover fiscal socialization and fiscal educational activity are significantly associated with both financial access and financial literacy, which are associated with positive financial behavior and negatively associated with economic hardship. We farther find that financial access plays a more important function in the arbitration effects decomposition than financial literacy. Based on our research findings, below nosotros summarize three fundamental points and talk over directions for hereafter policy and research.

Enhance Financial Capability: Provide Effective Financial Guidance and Education

Our results bear witness that both financial socialization and financial didactics are positively associated with financial literacy and fiscal education, leading to positive fiscal behavior, and decreased economic hardship. Thus, it is critical for policies and programs to implement effective financial education and guidance to enhance financial capability. Fiscal socialization occurs throughout life (Gudmunson & Danes, 2011); thus, people at all life stages could benefit from admission to guidance and didactics if more evidence points in this direction.

For now, evidence on the effectiveness of fiscal instruction is mixed. One report found that the effectiveness of financial teaching decays over time (Fernandes et al., 2014). Further, studies advise that "just in fourth dimension" and simplified dominion-of-thumb fiscal instruction that teaches financial heuristics that are like shooting fish in a barrel to sympathise, easier to follow, and stick with simple fiscal calculations are more effective than traditional financial education (Drexler et al., 2014; Fernandes et al., 2014; Mandell & Klein, 2009). Future research and do should continuously evaluate what, how, when, to whom fiscal education is effective in improving financial literacy and making people aware of available products and services.

Questions about the length of exposure and fashion of commitment remain for futurity inquiry: how many hours of financial education and financial guidance, offered in what way, can help everyone accomplish a basic level of financial literacy to make appropriate financial decisions? Conspicuously, more randomized experiments and quasi-experiments are needed to answer these questions (Collins & O'Rourke, 2010; Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2008). The answer to these questions may vary by group, such as people with low incomes, disabilities, racial and ethnic minority groups, immigrants, refugees, and others. Thus, having representative participants or oversampling minority groups is essential.

Multiple Components of Fiscal Capability for Policy, Research, and Practise

This study measures financial adequacy using multiple latent constructs: financial literacy (both subjective and objective), financial access, and financial behavior. Our findings from the measurement model suggest the multidimensional measurements of financial capability fit the data well. Policies and programs that aim to improve financial capability should consider multidimensional and nuanced aspects of fiscal adequacy. To build financial security and stability among households, policies and programs should consider individual and household ability to make optimized decisions and focus on opportunities to access and use mainstream fiscal services and products. Policies and programs should pay item attending to easing admission to fiscal products, services, and policies amidst vulnerable households at the bottom of the economic ladder who take been historically excluded from mainstream financial services.

Furthermore, future research should include more comprehensive and multidimensional measures of financial capability. Tradeoffs exist between financial adequacy measures: subjective versus objective measures, and unidimensional versus multidimensional with subcomponents. We use iii latent constructs—financial admission, financial literacy, and financial behavior—to capture the ability to deed and the opportunity to act as theorized in the financial adequacy framework. The current study aims to identify multidimensional measures relevant to the U.S. context, in line with Sherraden and Ansong's (2016) conceptualization that financial adequacy is multifaceted and context-specific. In the interest of advancing the broader awarding of the fiscal capability framework, more studies are needed to psychometrically validate this report'southward multidimensional measures' adequacy and utility. Futurity studies can adopt this approach and exam the validity and reliability of measures amidst diverse populations and diverse contexts to inform financial capability measurement development.

Importance of Financial Access and Financial Inclusion

Our indirect effect decomposition results revealed that financial access plays a relatively more predictive role than financial literacy in testing the pathways from financial socialization (guidance) and financial education to economic hardship. In other words, external institutional factors (i.e., opportunity to act) may be more than consequential than individual abilities and traits when aiming to better economic hardship. This finding confirmed our research hypothesis and is consequent with previous inquiry that supports institutional theories except that nosotros examine deportment and behavior that are beyond savings (e.k., Beverly & M. Sherraden, 1999; Beverly et al., 2008; Curley et al., 2009; M. Sherraden, 1991; 1000. Sherraden et al., 2003; Grand. Due south. Sherraden, 2013; Ssewamala & M. Sherraden, 2004; Sun et al., 2020). Farther, we extend this trunk of empirical piece of work that supports the financial capability framework (e.g., Huang et al., 2013, Westward & Frindline, 2016, Huang et al., 2013) by using a national representative sample of the U.Due south. population, tests of components and mechanisms of financial capability, besides as tests of both antecedents and outcomes of financial capability.

Practical ways to translate this finding into meaningful fiscal inclusion and admission should beginning by making sure all individuals and households accept ways to deposit money, emergency and long-term savings, investments, and affordable credit and insurance products. Further, these financial products should be advisable, accessible, affordable, financially bonny, easy to employ (with automatic features), flexible, secure, and reliable (Sherraden, 2013). Indeed, fiscal access and inclusion cannot be addressed one time and for all but instead require continued efforts. Birkenmaier et al. (2019) exposition on what it means to have financial admission suggests that a holistic approach is needed that addresses challenges when it comes to (a) having the legal right, necessary documentation, and eligibility, (b) ability to open, afford, and (c) opportunity to continually use financial products and services.

Scholars have made policy recommendations and proposals to aggrandize and improve financial admission and inclusion in key areas: emergency savings (Despard, Friedline, et al., 2018; Despard, Guo, et al., 2018; Despard, Taylor, et al., 2018); banking and financial services (Friedline et al., 2018); safe, affordable credit (Birkenmaier et al., 2018); likewise as utilizing technology and digital tools to make financial services easy to deliver (e.thousand., financial gateway and fintech; Huang, Nam, et al., 2016; Huang, Yard. Southward. Sherraden, et al., 2016). A critical lesson from these studies and the current study is that achieving fiscal inclusion requires efforts from multiple actors (due east.g., banks, credit unions, credit bureaus, loan funds, micro-lenders, and venture upper-case letter funds at local, state, and national level), the offering of multiple products and services and delivery at multiple settings (e.g., family setting, workplace, health care setting; Birkenmaier et al., 2019; Despard, Frank-Miller, et al., 2020; Despard, Grinstein-Weiss, et al., 2020). Discussions have emerged on integrating market place finance and social policy to make bones finance as a public skilful (Huang et al., 2021).

Limitations and Future Research

Five limitations are worth noting in this study. Below nosotros discuss these limitations and bespeak to directions for future research. First, this study uses cantankerous-exclusive, observational data; thus, the relationships information technology found are not causal. Developing causal evidence requires longitudinal studies. Challenges remain regarding data availability. 2nd, financial didactics and socialization measures used in this study are dichotomous self-reported measures. Time to come research should investigate the nuances of quality and intensity of financial education and socialization, which will require the evolution of financial education and socialization measurement scales. Third, we measured fiscal access by buying of financial products. However, Beverly et al. (2008) discussed ii aspects of access: eligibility and practicality. One may have admission but not own the product or vice versa; one might ain a financial production, merely the distance to get to the service is far (i.east., practicality is poor). Future research should measure financial admission beyond buying of products (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2008). Moreover, this report does not capture the social and psychological dimensions of fiscal access, such as perceptions of financial products and services and interactions with the staff of financial institutions (Despard & Chowa, 2014). Fourth, bi-directional relationships betwixt fiscal behavior and economic hardship may be; these are not examined in the present report. For example, families may develop coping strategies in response to economical hardship that focus on getting past in the brusque-term instead of developing long-term security and well-being. Further, feedback reinforcing loops may exist where well-off families reinforce positive beliefs and outcomes, whereas financially vulnerable households are caught in the adverse financial behavior and hardship spiral. Future research should test the potential bi-directional relationships and feedback loops using longitudinal data. This would provide empirical evidence to refine fiscal adequacy theory. Finally, data used in this study were collected in 2015 and and so may not reflect current financial capability and economic hardship weather among U.S. households. Yet, this study aimed to empirically test the financial capability framework rather than descriptively prove prevalence or trend, therefore the results are still applicable regarding relationships among constructs and the relative importance of financial access and financial literacy.

Conclusion

To conclude, this study is amidst the offset to empirically test the financial capability framework using a national representative sample. We find that financial guidance and financial instruction are positively associated with financial literacy and financial access, which lead to positive financial behaviors. Positive financial behaviors are, in turn, associated with reduced levels of economic hardship. We also find that financial access plays a more pronounced office in these relationships compared to financial literacy. Policies and programs should provide effective financial didactics and guidance to improve people'southward financial stability and well-beingness. More than attention should be paid to expanding fiscal access and promoting fiscal inclusion for all to have opportunities to achieve financial well-being and development.

Data Availability

Information used in this research can be downloaded at: https://world wide web.usfinancialcapability.org/

References

-

Allgood, S., & Walstad, Westward. B. (2016). The effects of perceived and actual fiscal literacy on financial behaviors. Economic inquiry, 54(1), 675–697. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12255

-

Barr, M. Due south., & Sherraden, M. West. (2005). Institutions and inclusion in saving policy. In N. Retsinas & Due east. Belsky (Eds.), Building assets, building wealth: Creating wealth in depression-income communities (pp. 286–315). Brookings Institution Press.

-

Beverly, S. Thousand., & Sherraden, Yard. (1999). Institutional determinants of saving: Implications for low-income households and public policy. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 28(four), 457–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-5357(99)00046-3

-

Beverly, Southward., Sherraden, K., Cramer, R., Williams Shanks, T., Nam, Y., & Zhan, M. (2008). Determinants of asset holdings. In Due south. M. McKernan & M. Sherraden (Eds.), Asset edifice and low-income families (pp. 89–152). Urban Found Press.

-

Birkenmaier, J., Despard, One thousand. R., & Friedline, T. (2018). Policy recommendations for fiscal capability and nugget building past increasing access to safe, affordable credit. Grand Challenges for Social Piece of work Initiative Policy Cursory, 11(two), 1–3.

-

Birkenmaier, J., Despard, Grand., Friedline, T., & Huang, J., et al. (2019). Financial inclusion and financial access. In C. Franklin (Ed.), Encyclopedia of social work. NASW Press and Oxford University Printing. https://doi.org/ten.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.1331

-

Birkenmaier, J., & Fu, Q. J. (2019). Does consumer financial management behavior relate to their financial access? Journal of Consumer Policy, 42(iii), 333–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-019-09418-z

-

Birkenmaier, J., Huang, J., & Kim, Y. (2016). Food insecurity and financial admission during an economic recession: Evidence from the 2008 SIPP. Journal of Poverty, 20(2), 194–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2015.1094767

-

Bradley, C., Burhouse, South., Gratton, H., & Miller, R. A. (2009). Alternative fiscal services: A primer. FDIC Quarterly, iii(1), 39–47.

-

Canilang, South., Duchan, C., Kreiss, One thousand., Larrimore, J., Merry, E., Troland, East., & Zabek, M. (2020). Report on economic well-being of US households in 2019, featuring supplemental data from April 2020. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Retrieved from https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2019-report-economic-well-existence-us-households-202005.pdf

-

Chowa, Grand., Ansong, D., & Despard, 1000. (2014). Fiscal capabilities for rural households in Masindi, Uganda: An exploration of the touch of internal and external capabilities using multilevel modeling. Social Work Research, 38(ane), 19–35. https://doi.org/x.1093/swr/svu002

-

Collins, J. G., & O'Rourke, C. K. (2010). Financial education and counseling: Even so holding promise. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44(3), 483–498. https://doi.org/x.1111/j.1745-6606.2010.01179.ten

-

Curley, J., Ssewamala, F., & Sherraden, M. (2009). Institutions and savings in low-income households. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 36(three), ix–32.

-

Danes, S. Chiliad., & Haberman, H. (2007). Teen financial cognition, cocky-efficacy, and beliefs: A gendered view. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, xviii(2), 48–lx.

-

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Brook, T. H. L., & Honohan, P. (2008). Finance for all policies and pitfalls in expanding access. A World Bank policy research report. World Banking company.

-

Despard, Grand. R., Friedline, T., & Birkenmaier, J. (2018, May). Policy recommendations for helping US households build emergency savings (Grand Challenges for Social Work initiative Policy Brief No. xi-three). American University of Social Work & Social Welfare. Retrieved from https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/csd_research/783/

-

Despard Grand., Grinstein-Weiss M., Chun Y., & Roll S. (2020, July 13). COVID-xix job and income loss leading to more than hunger and financial hardship. Brookings. https://world wide web.brookings.edu/blog/upward-front/2020/07/13/covid-19-job-and-income-loss-leading-to-more-hunger-and-financial-hardship

-

Despard, Yard. R., & Chowa, Chiliad. A. (2014). Testing a measurement model of financial capability among youth in Republic of ghana. Periodical of Consumer Diplomacy, 48(ii), 301–322.

-

Despard, M. R., Frank-Miller, Due east., Fox-Dichter, Southward., Germain, G., & Conan, M. (2020). Employee financial health programs: Opportunities to promote fiscal inclusion? Periodical of Customs Practise, 28(3), 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705422.2020.1796878

-

Despard, M. R., Guo, S., Grinstein-Weiss, G., Russell, B., Oliphant, J. E., & deRuyter, A. (2018). The mediating role of assets in explaining hardship risk among households experiencing financial shocks. Social Piece of work Research, 42(3), 147–158. https://doi.org/x.1093/swr/svy012

-

Despard, M. R., Taylor, South., Ren, C., Russell, B., Grinstein-Weiss, M., & Raghavan, R. (2018). Effects of a tax-fourth dimension savings experiment on cloth and health care hardship among low-income filers. Periodical of Poverty, 22(2), 156–178. https://doi.org/x.1080/10875549.2017.1348431

-

Drexler, A., Fischer, One thousand., & Schoar, A. (2014). Keeping it simple: Financial literacy and rules of thumb. American Economical Journal: Applied Economics, vi(2), ane–31. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.6.two.1

-

Elder, G. H., Jr., & Giele, J. Z. (2009). The arts and crafts of life course research. The Guilford Press.

-

Fernandes, D., Lynch, J. G., Jr., & Netemeyer, R. Chiliad. (2014). Fiscal literacy, financial education, and downstream financial behaviors. Direction Science, 60(viii), 1861–1883. https://doi.org/ten.1287/mnsc.2013.1849

-

Fong, R., Lubben, J., & Barth, R. P. (Eds.). (2017). Yard challenges for social work and gild. Oxford University Press.

-

Friedline, T., Despard, M. R., & Birkenmaier, J. (2018). Policy recommendations for expanding access to banking and fiscal services (K Challenges for Social Work initiative Policy Brief No. 11-4). American Academy of Social Piece of work & Social Welfare.

-

Gjertson, L. (2016). Emergency saving and household hardship. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 37(1), one–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-014-9434-z

-

Grinstein-Weiss, Thou., Despard, M., Guo, S., Russell, B., Primal, C., & Raghavan, R. (2016). Do revenue enhancement-time savings deposits reduce hardship amongst low-income filers? A propensity score assay. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 7(4), 707–728. https://doi.org/10.1086/689357

-

Gudmunson, C. G., & Danes, South. Chiliad. (2011). Family financial socialization: Theory and critical review. Journal of Family and Economic Problems, 32(4), 644–667. https://doi.org/ten.1007/s10834-011-9275-y

-

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(one), i–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

-

Huang, J., Nam, Y., & Lee, E. J. (2015a). Fiscal capability and economic hardship among low-income older Asian immigrants in a supported employment programme. Journal of Family unit and Economic Issues, 36(2), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-014-9398-z

-

Huang, J., Nam, Y., & Sherraden, Thousand. South. (2013). Financial knowledge and Kid Evolution Account policy: A test of fiscal capability. Periodical of Consumer Diplomacy, 47(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12000

-

Huang, J., Nam, Y., Sherraden, G., & Clancy, M. (2015b). Financial capability and asset aggregating for children'due south education: Prove from an experiment of child development accounts. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 49(1), 127–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12054

-

Huang, J., Nam, Y., Sherraden, K., & Clancy, M. One thousand. (2016). Improved financial capability can reduce material hardship among mothers. Social Work, 61(4), 313–320. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/sww052

-

Huang, J., Sherraden, One thousand. S., Clancy, M. One thousand., Sherraden, Chiliad., Birkenmaier, J., Despard, M., Frey, J., Callahan, C., & Rothwell, D. (2016). Policy recommendations for meeting the Chiliad Claiming to Build Financial Capability and Assets for All (Grand Challenges for Social Work Initiative Policy Brief No. 11). American Academy of Social Work & Social Welfare. https://doi.org/10.7936/K7057FG8

-

Huang, J., Sherraden, Yard. S., & Sherraden, M. (2021). Toward finance equally a public good (CSD Working Paper No. 21-03). Washington University, Center for Social Development. https://doi.org/ten.7936/p8dd-p256

-

Huston, Due south. J. (2010). Measuring financial literacy. Journal of Consumer Diplomacy, 44(2), 296–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2010.01170.x

-

Johnson, E., & Sherraden, M. S. (2007). From financial literacy to financial adequacy among youth. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 34(3), a7.

-

Jorgensen, B. L., & Savla, J. (2010). Financial literacy of immature adults: The importance of parental socialization. Family Relations, 59(four), 465–478. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00616.x

-

Kaiser, T., & Menkhoff, L. (2019). Fiscal educational activity in schools: A meta-assay of experimental studies. Economics of Education Review, 78, 101930. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.econedurev.2019.101930

-

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford.

-

Lusardi, A. (2011). Americans' fiscal capability (Working Newspaper, No. w17103). National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved from https://world wide web.nber.org/papers/w17103

-

Lusardi, A. (2019). Fiscal literacy and the demand for financial teaching: Testify and implications. Swiss Journal of Economics Statistics, 155(1), a1. https://doi.org/x.1186/s41937-019-0027-five

-

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2007). Fiscal literacy and retirement preparedness: Evidence and implications for financial instruction. Business organisation Economics, 42(one), 35–44. https://doi.org/x.2145/20070104

-

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2008). Planning and financial literacy. How do women fare? American Economic Review, 98(2), 413–417. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.98.2.413

-

Mandell, 50., & Klein, Fifty. S. (2009). The impact of financial literacy pedagogy on subsequent financial behavior. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, twenty(1), fifteen–24.

-

Martin, R. (2002). Financialization of daily life. Temple University Printing.

-

Nussbaum, M. C. (2001). Women and human evolution: The capabilities approach. University Press.

-

Nussbaum, M. C. (2011). Creating capabilities. Harvard Academy Printing. https://doi.org/x.4159/harvard.9780674061200

-

Parrott, S., Sherman, A., Llobrera, J., Mazzara, A., Beltrán, J., & Leachman, G. (2020, July 21). More relief needed to alleviate hardship: Households struggle to afford food, pay hire, emerging data show. Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. Retrieved from www.cbpp.org

-

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect furnishings in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/x.3758/BRM.forty.iii.879

-

Schuchardt, J., Hanna, S. D., Hira, T. Thousand., Lyons, A. C., Palmer, Fifty., & Xiao, J. J. (2009). Financial literacy and education research priorities. Journal of Fiscal Counseling and Planning, 20(ane), 84–95.

-

Sherraden, M. W. (1991). Avails and the poor: A new American welfare policy. M. Due east. Sharpe.

-

Sherraden, Grand. Due south. (2013). Building blocks of fiscal capability. Financial teaching and capability: Research, education, policy, and practice. In J. M. Birkenmaier, M. S. Sherraden, & J. C. Curley (Eds.), Financial capability and asset building: Enquiry, education, policy, and practice (pp. 3–43). Oxford University Printing.

-

Sherraden, Chiliad. South., & Ansong, D., et al. (2016). Fiscal literacy to financial capability: Building financial stability and security. In C. Aprea, Thousand. Breuer, & P. Davies (Eds.), International Handbook of Financial Literacy (pp. 83–96). Springer.

-

Sherraden, Thousand. S., & Huang, J., et al. (2019). Financial social work. In C. Franklin (Ed.), Encyclopedia of social work. Oxford Academy Printing. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.923

-

Sherraden, M. S., Huang, J., Jacobson Frey, J., Birkenmaier, J., Callahan, C., Clancy, Thou. 1000., & Sherraden, M. (2016). Financial capability and asset edifice for all (K Challenges for Social Work Initiative Working Paper No. 13). American Academy of Social Piece of work and Social Welfare.

-

Sherraden, M. Southward., & McBride, A. M. (2010). Striving to salve: Creating policies for financial security of low-income families. University of Michigan Press.

-

Sherraden, Thou., Schreiner, Thousand., & Beverly, South. (2003). Income, institutions, and saving performance in Individual Development Accounts. Economic Development Quarterly, 17(1), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891242402239200

-

Sherraden, M. South., Williams, T., McBride, A., & Ssewamala, F. (2004). Overcoming poverty: Supported saving as a household development strategy (CSD Working Paper No. 04-thirteen). Washington University, Heart for Social Evolution. https://doi.org/10.7936/K7N879C6

-

Ssewamala, F. Yard., & Sherraden, M. (2004). Integrating saving into microenterprise programs for the poor: Do institutions matter? Social Service Review, 78(3), 404–429. https://doi.org/10.1086/421919

-

Stacey, B. G. (1983). Economic socialization. British Periodical of Social Psychology, 22(3), 265–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.1983.tb00592.x

-

Stolper, O. A., & Walter, A. (2017). Financial literacy, financial advice, and financial behavior. Journal of Business concern Economics, 87(v), 581–643. https://doi.org/x.1007/s11573-017-0853-9

-

Lord's day, S., Nabunya, P., Byansi, W., Bahar, O. S., Damulira, C., Neilands, T. B., Guo, Southward., Namuwonge, F., & Ssewamala, F. M. (2020). Access and utilization of fiscal services among poor HIV-impacted children and families in Uganda. Children and Youth Services Review, 109, 104730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104730

-

Taylor, Thou. (2011). Measuring financial adequacy and its determinants using survey data. Social Indicators Research, 102(ii), 297–314. https://doi.org/x.1007/s11205-010-9681-9

-

Wang, J., & Wang, 10. (2012). Structural equation modeling: Applications using Mplus. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118356258

-

W, S., & Friedline, T. (2016). Coming of age on a shoestring upkeep: Financial adequacy and financial behaviors of lower-income millennials. Social Work, 61(iv), 305–312. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/sww057

-

Xiao, J. J., Chen, C., & Sun, 50. (2015). Age differences in consumer financial adequacy. International Periodical of Consumer Studies, 39(4), 387–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12205

-

Xiao, J. J., & O'Neill, B. (2016). Consumer financial education and fiscal capability. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 40(6), 712–721. https://doi.org/ten.1111/ijcs.12285

-

Xiao, J. J., & O'Neill, B. (2018). Propensity to plan, financial capability, and financial satisfaction. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 42(5), 501–512. https://doi.org/x.1111/ijcs.12461

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for FCAB for all m challenge network members across countries. We thank the Eye for Social Development and FCAB K Challenge Network Leadership's colleagues, including Julie Birkenmaier, Jodi Frey, David Rothwell, Christine Callahan, Lissa Johnson, Gena Gunn McClendon, and Michael Sherraden for their leadership and continued support over the years. We thank Shenyang Guo for hands-on and effective methodology trainings on Structural Equation Modeling. In addition, we thank Daniel Meyer, who moderated the presentation panel at the SSWR conference and provided constructive comments, every bit well as audiences from the FCAB 5th convening for their helpful feedback. Finally, nosotros appreciate the reviewers' comments, which improved an earlier version of this commodity.

Funding

The authors received no fiscal support for this enquiry.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors are not enlightened of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived every bit affecting the objectivity of this research.

Ethical Blessing

NA.

Informed Consent

Not applicable. This research utilizes secondary data.

Consent to Participate

NA.

Consent for Publication

All authors have approved the manuscript and agree with its submission to the journal.

Research Involving Human and/or Creature Participants

Not applicable.

Additional data

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This is one of several papers published together in Journal of Family and Economical Issues on the "Special Issue on Fiscal adequacy and asset building for family financial wellbeing".

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, Southward., Chen, YC., Ansong, D. et al. Household Financial Adequacy and Economic Hardship: An Empirical Exam of the Financial Capability Framework. J Fam Econ Iss (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-022-09816-5

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1007/s10834-022-09816-five

Keywords

- Financial access

- Financial literacy

- Fiscal behavior

- Cloth hardship

- Financial inclusion

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10834-022-09816-5

0 Response to "To what extent does financial capability factor into the issue of hunger? Why?"

Post a Comment